Painter

Ronald Davis returns from obscurity

By Kyle MacMillan

Denver Post Critic-at-Large

Thursday, November 14, 2002

Young artists sometimes burst into the national spotlight, enjoy a decade or so of intense attention before the art world seems to move on, and then all but disappear from view.

Some years later, these same artists are suddenly rediscovered, even though they had been making and showing work all along, and are touted as something akin to modern old masters.

This phenomenon certainly affected painters such as Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis, who fell almost completely out of favor and are now very much back in vogue.

Something similar could well be about to happen to the once widely known abstract painter Ronald Davis, 65, of Arroyo Hondo, N.M., whose name these days often elicits a look of puzzlement even from art-world professionals.

Gwen Chanzit, a Denver Art Museum curator of modern and contemporary art, has organized an exhibition of his recent work at the University of Denver, which has been extended through Sunday.

And at the same time, the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio, is presenting a retrospective titled "Ronald Davis: Forty Years of Abstraction 1962–2002."

The big moment for Davis, who was born in Santa Monica, Calif., and grew up in Cheyenne, came in the 1960s and '70s. If he never quite made the A-list of artists, he came close.

He was featured in a 1968 solo show at Leo Castelli in New York City, arguably the most important gallery of the time, and several major museums purchased his works that year.

Despite his success, Davis faded out of sight. The last solo exhibition he lists took place seven years ago at DEL Fine Arts in Taos.

Davis gained recognition for abstract paintings that shared similarities with optical art in that they had an illusionistic or trompe l'oeil quality that tricked the eye by using vanishing-point perspective to suggest three-dimensionality where none actually existed.

As the decades went by, his employment of a perspective grid grew more rigorous and complex as he began to use three-dimensional computer programs to assist him in the process.

But in the 24 acrylic paintings that make up the main body of his show at DU, he has made a surprising U-turn, largely abandoning vanishing-point perspective and returning to a earlier, freer style.

"Illusion remains," he writes in an exhibition statement, "but these paintings are more optical and elusive; given looking time, they move around a lot in subtle, ambiguous and mysterious ways."

Although a few of these images suggest recognizable objects such as "I-Beam" or "Blue-Violet Slab," most of these works take on asymmetrical, off-balance and sometimes sprawling shapes which are all but impossible to describe.

All of these works are relief paintings, which is to say that they all are painted on "boxes" that Davis has painstakingly constructed out of cut and glued sheets of polyvinyl chloride, a type of hard plastic. They jut 1 to 3 inches from the wall, with beveled sides.

The painting surfaces are consistently flat, but because of the trompe l'oeil effects that Davis achieves with intersecting planes of color, some of the works appear to have raised or lowered sections.

All of these

works are relief paintings, which is to say that they all are painted

on "boxes" that Davis has painstakingly constructed out of cut

and glued sheets of polyvinyl chloride, a type of hard plastic. They jut

1 to 3 inches from the wall, with beveled sides.

The painting surfaces are consistently flat, but because of the trompe

l'oeil effects that Davis achieves with intersecting planes of color,

some of the works appear to have raised or lowered sections.

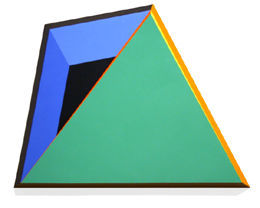

Such an illusion can be seen in "Green Triangle Overlay," an

angled, four-sided piece, which is one of most striking works in the show.

Two similarly shaped, purple trapezoidal sections collide on the upper

left side in such a way that they seem be elevated a few inches from the

surface.

In nearly all these pieces, Davis employs unexpected and often jarring

combinations of bold colors, which have been so fastidiously applied with

a roller that the uniformly textured surfaces take on a machinelike perfection.

It is a visually engaging group of works that remind viewers why Davis

was once celebrated in the art world and why his day will likely come

again.

Abstract master

What: 'Ronald

Davis: Recent Abstractions 2001-2002,'

painting exhibit.

When: Sept. 13 – Nov. 17, 2002

Where: Victoria H. Myhren Gallery, University of Denver, Shwayder Art

Building, 2121 E. Asbury Ave. Denver, CO

Admission: Free; call 303-871-2846

Ronald Davis, Green Triangle Overlay, 2002