ARTFORUM

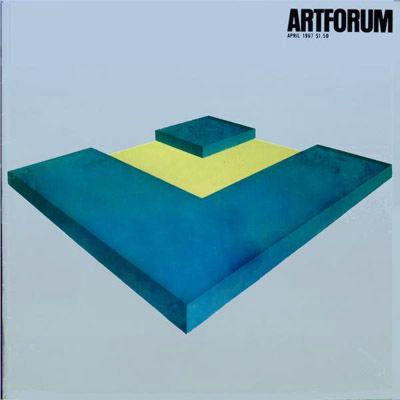

Cover: Six-Ninths

Blue, 1966, 72 x 131 inches

Polyester Resin, Fiberglass, and Wood

Polyester Resin, Fiberglass, and Wood

RONALD DAVIS: Surface and Illusion

MICHAEL FRIED

Originally published in ARTFORUM, Volume V. No. 8, April 1967

Ron Davis is a young California artist whose new paintings, recently shown at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York, are among the most significant produced anywhere during the past few years, and place him, along with Stella and Bannard, at the forefront of his generation. In at least two respects Davis' work is characteristically Californian: it makes impressive use of new materials — specifically, plastic backed with fiberglass — and it exploits an untrammeled illusionism. But these previously had yielded nothing more than extraordinarily attractive objects, such as Larry Bell's coated glass boxes, or ravishing, ostensibly pictorial effects, as in Robert Irwin's recent work. (In the first instance illusion is rendered literal, while in the second it dissolves literalness entirely.) Whereas Davis' new work achieves an unequivocal identity as painting. That this is so is a matter of conviction. One recognizes Davis' new work as painting: in my case, with amazement — and, at first, distrust, even resentment — that what I was experiencing as paintings were, after all, made of plastic. Not that Davis' paintings are what they are in spite of being made of plastic or presenting a compelling illusion of a solid object in strong perspective. On the contrary, it is precisely Davis' refusal to settle for anything but ambitious painting that, one feels, has compelled him to use both new materials and two-point perspective. What incites amazement is that that ambition could be realized in this way — that, for example, after a lapse of at least a century, rigorous perspective could again be come a medium of painting. Davis' paintings are, I suggest, the most extreme response so far to the situation described in my essay Shape as Form: Frank Stella's New Paintings.1 Roughly, Davis has used perspective illusion -- the illusion that the painting as a whole is a solid object seen in two-point perspective from above -- to relieve the pressure under which, within that situation, the shape of the support (or literal shape) has come to find itself. The limits of Davis' new paintings present themselves as the edges of a three-dimensional entity rather than of a flat surface; and in fact it is virtually impossible to grasp the literal shape of paintings like Six-Ninths Blue and Six-Ninths Red just by looking at them. (One is forced, so to speak, to trace their limits and then see what one has.) As a result, the question of whether or not the literal shapes of Davis' new paintings hold, or stamp them selves out, or compel conviction a burning question within the situation referred to Ê simply does not arise. More precisely, it does not arise as long as the illusion of three dimensionality remains compelling: if, in a given painting, for whatever reason; the illusion is felt to be in jeopardy, that painting's ability to hold as shape is rendered question able as well. (Something of the kind may happen in Two-Ninths Grey, in which the projected object is not, to my mind, sufficiently comprehensible. What, for example, is the precise relation of the two gray blocks to the larger red slab on which they seem to sit? In general, Davis can not afford much ambiguity or indeterminacy, both of which compromise his paintings' apparent objecthood.)A great deal, then, depends upon the power of the illusion; and it was, I believe, in order to achieve that power that Davis gave up working in paint on canvas and began to explore the possibility of making his new paintings in plastic. In any case, the fact that in his new paintings color is not applied to the surface in any way, but instead seems physically to lie somewhere behind it, makes the illusion of objecthood infinitely more compelling than would otherwise be the case. In this respect Davis' new paintings represent not only an inspired resuscitation of, but a deep break with, traditional illusionism: in the latter paint on the surface of the canvas creates the illusion of objects in space; while in Davis' paintings whatever makes the illusion is not, it seems, situated on, or at, the surface at all. (The illusion of objecthood is intensified still more by the way in which the colored plastic — in which Davis has also mixed mirror flake, aluminum powder, bronze powder and pearl essence — not merely represents but imitates the materiality of solid things.) Conversely, the surface of these paintings is experienced in unique isolation from the illusion. It has been prized loose from the rest of the painting - as though what hangs on the wall is the surface alone. In Davis' new paintings a detached surface coexists with a detached illusion. (In this respect his paintings are the opposite of Olitski's, in which there is "an illusion of depth that somehow extrudes all suggestions of depth back to the picture's surface."2) Indeed, the detached surface coincides with the detached illusion: which is why the question of whether or not the shape of that surface holds or stamps itself out does not arise. Davis deliberately — and, I think, profoundly — heightens one's sense of the mutual independence of surface and illusion by rather sharply beveling the edges of his paintings from behind. This means that even when the beholder is not standing directly in front of a given painting, no support of any kind can be seen. The surface is felt to be exactly that, a surface, and nothing more. It is not, one might say, the surface of anything — except, of course, of a painting.

Moreover, Davis' surface is some thing new in painting: not because it is shiny and reflects light — that was also true of the varnished surfaces of the Old Masters — but be cause what one experiences as surface in these paintings is that reflectance and nothing more. The precise degree of reflectance is important. If the painting is too shiny the surface is emphasized at the expense of the illusion; and this in turn under mines the independence of both. At the same time, Davis' paintings make transparency important as never be fore: not because their surfaces are experienced as transparent — one does not, I want to say, look through so much as past them3 — but because the layers of colored plastic behind their surfaces vary in opacity. The relation between the surface and the rest of a transparent object is different from that between the surface and the rest of an opaque one: roughly, in the former case it is as though the beholder can see all of the object, not just the portion that his eyesight touches. In Davis' new work this difference becomes important to painting for the first time, by making possible, or greatly strengthening, the relation between surface and illusion that I have tried to describe.

Finally, I want at least to touch on the character of the illusionism in these paintings. Despite its dependence on the rigorous application of two-point perspective, it, too, is new in painting. Roughly, the illusion is of something one takes to be a square slab (some portions of which have been removed), turned so that one of its corners points in the general direction of the beholder, and seen from above. What seems to me of special interest is this: the illusion is such that one simply assumes that the projected slab is horizontal, as though Laying on the ground; but this means that looking down at it could be managed only from a position considerably above both the slab itself and the imaginary ground-plane it seems to define. Moreover, the beholder is not only suspended above the slab; he is simultaneously tilted toward it — otherwise he would not be in a position to look down at the slab at all. In Davis' new paintings the illusion of objecthood does not excavate the wall so much as it dissolves the ground under one's feet: as though experiencing the surface and the illusion independently of one another were the result of standing in radically different physical relations to them. Davis' illusionism addresses itself not just to eyesight but to a sense that might be called one of directionality. There have been strong intimations of such a development in recent painting, notably that of Noland and Olitski; in fact, I recently claimed of Olitski's spray paintings that what is appealed to is not our ability in locating objects (or failing to) but in orienting ourselves (or failing to).4 This seems to me dramatically true of Davis' new paintings as well.

The possibilities which Davis has been able to realize in his first plastic paintings still seem to me scarcely imaginable. The possibilities which they open up belong to the future of painting.

1. ARTFORUM Vol. 5, No. 3, November 1966.

2. Clement Greenberg, in the catalog to the United States Pavilion in the 1966 Venice Biennial.

3. Not the way one looks past an object so much as the way one looks past a reflection .

4. In the catalog essay to Olitski's forthcoming exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery.