|

|

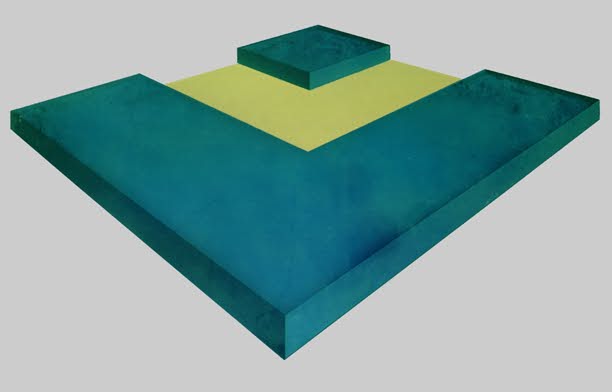

A Note on Ron Davis' Illusionism

Six-Ninths Blue, 1966

72 x 131 x 3 inches (shaped)

Polyester Resin, Fiberglass, and Wood

![]() Our

visual systems are exquisitely sensitive to information about the shapes

of objects, including depth within an object, that is, which parts are

farther and which closer. Consider a piece of paper lying on a table.

You can easily tell which side is closest to you. How does your brain

know? In other words, what information is available to construct your

percept? This information comes in several forms, which are often called "visual

depth cues." One cue comes from stereoscopic vision. Slight differences

in the two eyes' retinal images are interpreted as depth by the brain.

Another cue comes from an unconscious assumption that the paper is a

rectangle. This cue is a variant of the "linear perspective" cue. (Try

this: trim a thin triangular wedge from one side of a rectangular piece

of blank paper. Put it on a table or surface that doesn't have much texture.

Look at it from a sharp angle [not from overhead] with just one eye.

Looks like a rectangle, doesn't it?) Another cue is height within the

visual field — objects that are seen from above (things on tables

and floors, for example) are generally farther from you if they are higher

in the visual field. Now, notice that those last two cues almost always

tell you the correct answer as to what's near and what's far, for real

objects in the real world. They are what vision scientists call "statistically

valid." Because they almost always give correct information, it makes

sense for the brain to pay attention to them and use them during percept

construction. Just as it's statistically valid, but not logically necessary,

to conclude there was a power failure if the alarm clocks, microwave

oven display, and VCR are all blinking when you get home (it's unlikely,

but possible, that a cat jiggled all the plugs instead). Now, what if

a clever artist were to construct, artificially, a peculiar but very

real object in which the depth cues give false testimony? Your brain

brain would be perfectly right to conclude that the most likely object,

the one it should construct in the percept, is not the real object but

the one suggested by the cues.

Our

visual systems are exquisitely sensitive to information about the shapes

of objects, including depth within an object, that is, which parts are

farther and which closer. Consider a piece of paper lying on a table.

You can easily tell which side is closest to you. How does your brain

know? In other words, what information is available to construct your

percept? This information comes in several forms, which are often called "visual

depth cues." One cue comes from stereoscopic vision. Slight differences

in the two eyes' retinal images are interpreted as depth by the brain.

Another cue comes from an unconscious assumption that the paper is a

rectangle. This cue is a variant of the "linear perspective" cue. (Try

this: trim a thin triangular wedge from one side of a rectangular piece

of blank paper. Put it on a table or surface that doesn't have much texture.

Look at it from a sharp angle [not from overhead] with just one eye.

Looks like a rectangle, doesn't it?) Another cue is height within the

visual field — objects that are seen from above (things on tables

and floors, for example) are generally farther from you if they are higher

in the visual field. Now, notice that those last two cues almost always

tell you the correct answer as to what's near and what's far, for real

objects in the real world. They are what vision scientists call "statistically

valid." Because they almost always give correct information, it makes

sense for the brain to pay attention to them and use them during percept

construction. Just as it's statistically valid, but not logically necessary,

to conclude there was a power failure if the alarm clocks, microwave

oven display, and VCR are all blinking when you get home (it's unlikely,

but possible, that a cat jiggled all the plugs instead). Now, what if

a clever artist were to construct, artificially, a peculiar but very

real object in which the depth cues give false testimony? Your brain

brain would be perfectly right to conclude that the most likely object,

the one it should construct in the percept, is not the real object but

the one suggested by the cues.

![]() This

is what happens in a piece like Six-Ninths Blue by Ron Davis.

The linear perspective cue, and the height-in-visual-field cue, tell

you that the top of the object is much farther away than the bottom

(even though it's not). The perspective is nearly identical to that

produced by a square-footprint object, seen from just above ground

level. In fact, the object has a second perceptual effect: it changes

your idea of where the ground is. It's the fact that we see things

correctly almost all the time that makes illusions of depth so fascinating.

Objects that have invalid depth cues are pretty rare. Unless you're

an artist who creates such objects, and therefore sees them all the

time — Davis is not as susceptible to his own illusions as he

used to be. That we fall prey to them is a tribute to our brains' amazing

ability to figure out, for the most part correctly, what cues are reliable

indicators of depth.

This

is what happens in a piece like Six-Ninths Blue by Ron Davis.

The linear perspective cue, and the height-in-visual-field cue, tell

you that the top of the object is much farther away than the bottom

(even though it's not). The perspective is nearly identical to that

produced by a square-footprint object, seen from just above ground

level. In fact, the object has a second perceptual effect: it changes

your idea of where the ground is. It's the fact that we see things

correctly almost all the time that makes illusions of depth so fascinating.

Objects that have invalid depth cues are pretty rare. Unless you're

an artist who creates such objects, and therefore sees them all the

time — Davis is not as susceptible to his own illusions as he

used to be. That we fall prey to them is a tribute to our brains' amazing

ability to figure out, for the most part correctly, what cues are reliable

indicators of depth.

Benjamin

T. Backus

Professor of Psychology

University of Pennsylvania

backus@psych.upenn.edu

|

|